-----------------------------------------

Responding to Vox’s popular: “America’s unique gun violence problem, explained in 17 maps and charts”

An article at Vox has gained attention for illustrating America’s “unique gun violence problem” in 17 maps and charts. Below, we will respond to the individual graphs below on Vox’s terms. But there are a lot of assumptions behind Vox’s graphs. Often just one or two public health studies are cited to make a particular point, without discussing any of the known weaknesses with these studies or acknowledging and critiquing research that shows the opposite of the conclusion that they would like to reach.

Economists focus on the notion of substitution. If you take away guns, people might commit suicides or murders in other ways. It is total deaths that need to concern everyone. Vox and focus exclusively on gun deaths without looking at the larger picture.

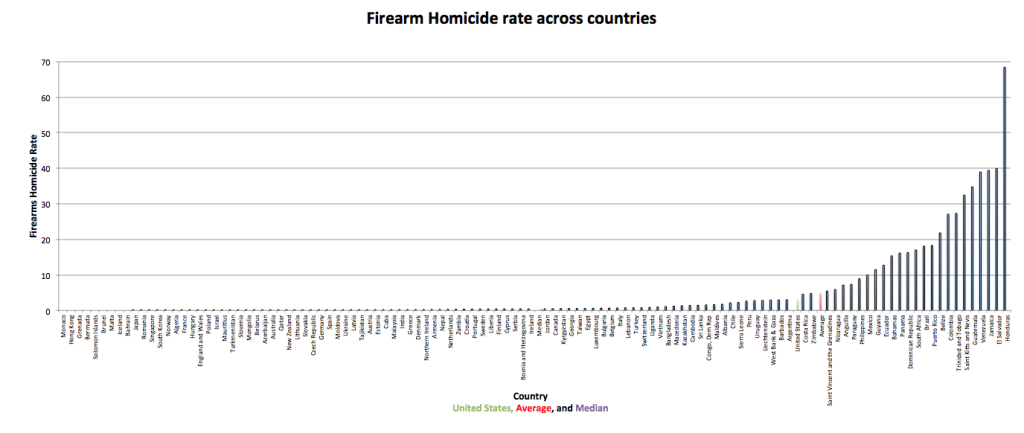

There are many countries that have higher gun homicide rates than the United States, but simply don’t report firearm homicide data. Many of these meet the criteria to be members of the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). While 192 countries report total homicides, only 116 countries report firearm homicides. The average homicide rate among countries that don’t have firearm homicide data is 11.1 per 100,000.

Homicide is not synonymous with murder. Homicides count both murders and justifiable homicides (when a police officer or a civilian kills someone in self-defense). In the five years from 2011 to 2015, the US experienced 11,577 firearm homicides and 8,786.4 firearm murders. This gap is much larger in the US than in other countries, so comparing homicide rates gives a more unfavorable impression of the US than if we looked only at murder rates.

Murder isn’t a nationwide problem in the United States; it’s a problem in a very small set of urban areas. In 2014, the worst 2 percent of counties accounted for 52 percent of the murders. Five percent of counties accounted for 68 percent of the murders. Even within these counties, there are large regions without any murders. Clearly, drug gangs have contributed a lot to the violent crime problems in America’s cities. Many of these gangs have easy access to illegal guns.

The popular press likes to compare crime rates in different places at the same point in time. But academics are aware of the limitations of this simple, cross-sectional comparison. Gun control advocates often compare the US and the UK, pointing out that the UK has stricter gun control and lower homicide rates than the US. Omitted is the fact that the UK’s homicide rate went up after its gun control laws were enacted.

The UK’s homicide rate was still lower than the US’s, but it was despite the country’s counterproductive gun control laws, not because of them. The homicide rate was very low even before the UK had any gun control laws. To understand the effects of the laws, we have to see how homicide rates change before and after their implementation. Then, we can compare these changes in crime rates with the changes in places that didn’t reform their laws.

One thing gun control advocates such as Vox would never mention is that every single time that guns have been banned — either all guns or all handguns — homicide/murder rates rise. This is a remarkable fact. One would think that just due to random chance, one or two countries would have a drop in homicides after banning guns.

Vox also has video that differs from the graphs that they have in the text. In particular, they start out of with a discussion on mass public shootings using data collected by Jaclyn Schildkraut of the State University of New York-Oswego and H. Jaymi Elsass, a researcher at Texas State University. Unfortunately, in December 2015, when it was pointed out that their list was missing a lot of cases Washington Post “Fact Checker” reporter Michelle Lee wrote Dr. Lott: “[Schilkraut] said they are still adding cases, and that it’s not a complete database.” However, Schilkraut and Elsass had already gone public with their findings about how the U.S. compared to other countries. They did so with full knowledge that they were missing many shootings in foreign countries. Not only did they miss cases, but Vox also doesn’t put the numbers for different countries on a per capita basis. It is startling that Vox puts other numbers in per capita terms, but not these numbers.

Here is a much more complete list of mass public shootings in the US. For cases around the world see here.

Responding to Vox’s graphs.

1) Claim #1: “America has six times as many firearm homicides as Canada, and nearly 16 times as many as Germany”

They offer no explanation for why they compare only these 14 countries. OECD, the club of developed countries, has 34 countries. There are 192 countries for which homicide data is available.

Here are homicide rates across all countries for which data is available (click on figures to enlarge). Even given the problems with homicide data not being underreported in many countries, the US homicide rate is less than the median rate and half of the mean average for all countries.

Now let’s look at the much smaller number of countries that report firearm homicide rates. The US rate looks much higher relative to other countries, but that is primarily because the countries with the highest homicide rates are the ones that don’t report their firearm homicide rates.

Using the OECD numbers, here is how homicide rates vary. The countries with the highest homicide rates don’t even report firearm homicides and these same countries have very strict gun control regulations.

The US homicide rate is high, though the most important question here is how homicide rates vary with gun ownership. Vox doesn’t deal with this until point #6. Since it pertains to the homicide data that we have just discussed, we will address it here.

2) Claim #6: “It’s not just the US: Developed countries with more guns also have more gun deaths”

Here is the same figure for homicides generally, rather than just firearm homicides. Brazil, Mexico, and Russia are excluded. It uses the Small Arms Survey numbers despite the survey’s dramatic underestimation of gun possession rates in countries such as Israel and Switzerland, where guns possessed for decades by individuals are technically owned by the government. We will later show how these problems bias the results towards what Vox wants to show.

The claim that more guns mean more gun deaths for countries besides the US is simply false. Once the US is excluded, the relationship across all the other countries shows that more guns mean fewer homicides.

Note that you can also get a negative relationship across countries with the US, if Brazil and Russia are also included.

Some might object to including OECD-member Mexico as a developed country, but including it produces and an even more negative relationship.

Similarly, increasing the reported measure of firearms per 100 people for two low-homicide countries (Israel and Switzerland, to reflect the possession of guns at home) will also make this relationship negative even when the US is included and Brazil, Mexico, and Russia are excluded.

When we look at all of the surveyed countries, the Small Arms Survey shows an association between more guns and fewer homicides.

The same is true for the much smaller set of countries that report firearm homicides.

3) Claim #2: “America has 4.4 percent of the world’s population, but almost half of the civilian-owned guns around the world”

As mentioned earlier, countries such as Israel and Switzerland have a lot more civilian-possessed guns than civilian-owned guns. In these two countries, the gun possession rate is higher than the gun ownership rate in the US. But there is a bigger accuracy problem in counting gun ownership using surveys or gun registration. There is strong evidence that most guns are never registered.

When Canada tried to register its estimated 15 million to 20 million long guns during the late 1990s, about 7 million were registered. In the 1970s, German registration recorded 3.2 million of the country’s estimated 17 million guns. In the 1980s, England registered pump-action and semiautomatic shotguns, but only about 50,000 of the estimated 300,000 such guns were actually registered.

Even in the US, there is evidence that surveys of gun ownership rates are not very accurate. In many countries where gun ownership is illegal, surveys continually show zero gun ownership even when that is clearly not the case.

The bottom line is that the numbers of guns in the rest of the world is underestimated relative to the number in the United States. So 42% is likely a huge overestimate of the US’s true share of guns worldwide.

4) Claims #3 and #4: “There have been more than 1,600 mass shootings since Sandy Hook” and “On average, there is around one mass shooting for each day in America”

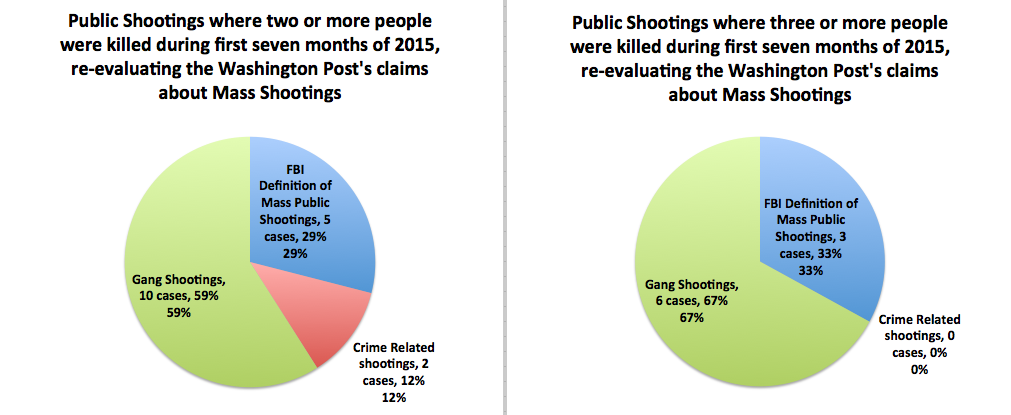

As Vox notes: “The tracker uses a fairly broad definition of ‘mass shooting’: It includes not just shootings in which four or more people were murdered, but shootings in which four or more people were shot at all (excluding the shooter).” The FBI has used two different definitions: mass shootings and mass public shootings. Vox’s definition of a mass public shooting differs dramatically from the traditional FBI definition of in other ways. In particular, the FBI excludes cases of gangs fighting against each other in order to focus on those cases where the point of the attack was to kill people. The FBI wanted to focus on the types of mass public shootings that we see at schools, malls, and other public places. This isn’t to say that gang fights over drug turf aren’t important, but the causes and solutions for them are dramatically different than for the mass public shootings that we hear about on the news.

Here is an earlier post that we put up:

5) Claim #5: “States with more guns have more gun deaths”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10259683/mother_jones_gun_deaths_by_state.png)

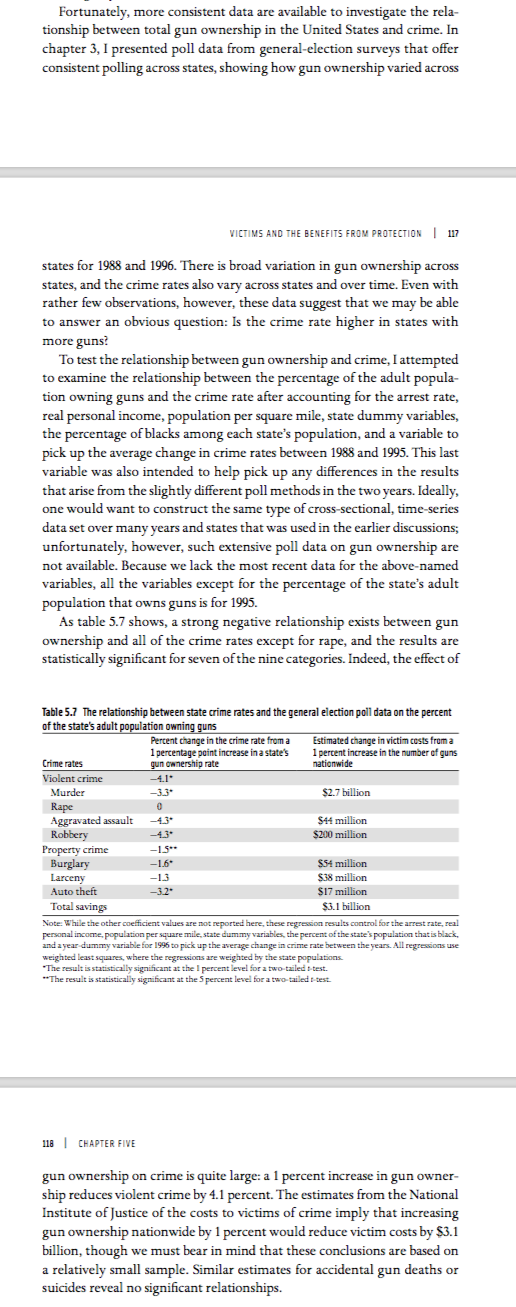

This figure uses purely cross-sectional data, looking at all these states at just one point in time. But to do a proper analysis, one has to see how crime rates vary over time across all the states. Did the states that had the biggest increases in gun ownership have the biggest increases or decreases in crime rates? Here is part of a discussion from Dr. John Lott’s “More Guns, Less Crime” (University of Chicago Press, 2010).

6) Claim #7: “America is an outlier when it comes to gun deaths, but not overall crime”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10328651/CRIME_15_COUNTRIES_US.jpg)

While the graph doesn’t directly show the point that Vox is raising, their claim is: “the US appears to have more lethal violence — and that’s driven in large part by the prevalence of guns.”

The United States has a relatively low violent crime rate compared to other developed countries. The graph below includes the average violent crime rate across these countries (a separate break down by sexual assault, robbery, and assault is available here). Compared to those countries the United States does have a relatively high homicide rate. But Vox doesn’t even discuss the most obvious explanation: that the US has a bad drug gang problem.

7) Claim #8: “States with tighter gun control laws have fewer gun-related deaths”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9371423/gun_control_vs_deaths.jpg)

As with our earlier discussions, purely cross-sectional comparisons can be very misleading. A detailed discussion is available here. The graph below is what you get once you account for national changes in crime rates and pre-existing differences across states.

8) Claim #9: “Still, gun homicides (like all homicides) have declined over the past couple decades”

This is correct.

9) Claim #10: “Most gun deaths are suicides”

Most firearm deaths are indeed suicides. But Vox lumps together murders and justifiable homicides into the category of “firearm homicides.” Obviously, justifiable homicides should be counted differently from murders.

10) Claim #11: “The states with the most guns report the most suicides”

Once again, Vox’s use of purely cross-sectional comparisons can be very misleading. Vox tries to show that states with high guns ownership have high suicide rates, but they ought to consult a notable economics paper on suicide by Cutler, Glaeser, and Norberg. Cutler, et al. found that rural areas have both a large male-female population imbalance and also more gun ownership. They found the real cause to be the high number of partnerless, older men.

Instead of relying on surveys of gun ownership, we can use the number of concealed handgun permits as a proxy for ownership. And when we use panel data to follow states over time, we see no association between suicides and the number of concealed handgun permits.

There is a strong tendency for states with more gun control laws to have lower gun ownership rates. Yet, doing this research properly, we find that more gun laws are associated with more total suicides and are unrelated to firearm suicides.

11) Claim #12: “Guns allow people to kill themselves much more easily”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9371561/fatal_suicide_attempts.jpg)

Vox argues: “Perhaps the reason access to guns so strongly contributes to suicides is that guns are much deadlier than alternatives like cutting and poison.”

But Vox gives a very misleading impression of the effectiveness of different suicide methods. A 1995 study looked at 4,117 cases of completed suicide in Los Angeles County during the period 1988-1991, and found that the success rate for being hit by a train is virtually the same as for a gunshot to the head or a shotgun to the chest. The study also estimated that the amount of pain and discomfort from being hit by a train was about half of either of those methods.

The second problem with these numbers is that not everyone wants to successfully commit suicide, so people can affect the success rate of the method. They may take a few extra pills, but not enough to actually kill themselves.

12) Claim #13: “Policies that limit access to guns have decreased suicides”

Vox cites two studies claiming that gun control laws can reduce suicides. One study is on Australia’s 1996/97 gun buyback and another is on Israel. But cherry-picking two studies isn’t very useful. Vox just ignores research that doesn’t support their conclusions.

This is part of a longer piece that Dr. John Lott wrote up on Australia’s buyback program (an entire chapter in “The War on Guns” covers this topic):

But looking at simple before-and-after averages of gun deaths in Australia regarding the gun buyback is extremely misleading. Firearm homicides and suicides were falling from the mid-1980s onwards, so you could pick out any subsequent year and the average firearm homicide and suicide rates after that year would be down compared to the average before it.The question is whether the rate of decline changed after the gun buyback law went into effect. But the decline in firearm homicides and suicides actually slowed down after the buyback.Australia’s buyback resulted in almost 1 million guns being handed in and destroyed, but after that private gun ownership once again steadily increased and now exceeds what it was before the buyback.In fact, since 1997 gun ownership in Australia grew over three times faster than the population (from 2.5 million to 5.8 million guns).Gun control advocates should have predicted a sudden drop in firearm homicides and suicides after the buyback, and then an increase as the gun ownership rate increased again. But that clearly didn’t happen. . . .

The Israeli study is poorly done. In 2006, Israel soldiers were stopped from taking their guns home with them on weekends. There was a drop in suicides in 2007-2008 compared to 2003-2005, but a better study would have compared soldiers who could have taken their guns home with those who couldn’t. The study uses only simple before-and-after averages, similar to the Australian comparisons. No month-to-month changes are provided, so it isn’t clear exactly when the drop in suicides started.

A similar issue has already been tested in the proper way. Permitted concealed carry is analogous to soldiers being able to take their guns home with them. And the researchfinds no increase suicides when people are allowed to carry their handguns with them.

Vox selectively picks research and ignores that some gun control regulations, such as gunlock laws, actually cause an increase in total deaths. In the case of locks, guns are made less accessible for self-defense.

13) Claim #14: “In states with more guns, more police officers are also killed on duty”

Vox cites a study in the American Journal of Public Health which claims that states with more guns also have more cops die in the line of duty. Unfortunately, this study is particularly fraudulent. There are normal controls to account for average differences across places and across years, and this study only accounts for the average differences across places. If both factors were accounted for, as is always done in this research, the authors would have gotten the opposite results from what they claim.

14) Claim #15: “Support for gun ownership has sharply increased since the early 2000s”

There are a number of surveys that show support for gun control peaked around 1998 and 1999. The Pew survey that Vox cites is just one such survey. Why they cut off the survey data in 2000 and don’t go back further is a puzzle that only Vox can answer. The Gallup and CNN surveys are available here.

15) Claim #16: “High-profile shootings don’t appear to lead to more support for gun control in the long term”

The key here is “long-term.” It is the reason why gun control groups try in the short-term to push through gun control soon after shootings.

16) Claim #17: “Specific gun control policies are fairly popular”

Given the supposed 90% support that the media tells us exists for expanded background checks, one would think that Michael Bloomberg’s well-funded ballot initiatives in 2016 in Nevada and Maine would have been slam dunks. Yet, Bloomberg lost in Maine by 4 percent and won in Nevada by just 0.8 percent (and only then because Bloomberg’s people incorrectly promised that passing the initiative wouldn’t cost the state anything). Bloomberg’s initiative only eked out the win in Nevada because of the $20 million spent in support of it, amounting to an incredible $35.30 per vote. He outspent his opponents by a factor of three – in Maine, the $8 million he spent outdid the other side by a factor of six.

No comments:

Post a Comment